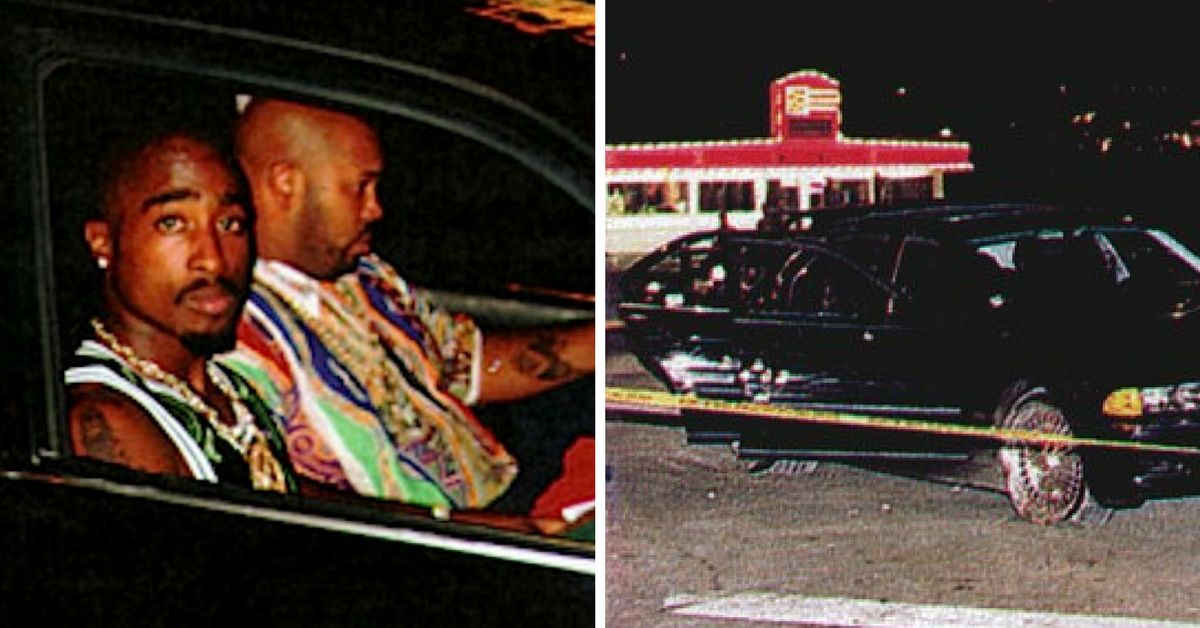

Biggie Smalls Death Scene

Attack type, Weapons Blue-steel (exact model and make unknown) Deaths 1 (Christopher Wallace, a.k.a. 'The Notorious B.I.G.' ) Perpetrator Unknown The murder of Christopher Wallace, better known by his stage names ' and 'Biggie Smalls', occurred in the early hours of March 9, 1997. The artist was shot four times in a in, one of which was fatal. Despite numerous witnesses and enormous media attention and speculation, no one was ever formally charged for the murder of Wallace. The case remains officially unsolved, as police have searched for years for more details without success.

In 2006, Wallace's mother, Voletta Wallace; his widow, Faith Evans and his children, T'yanna Jackson and Christopher Jordan Wallace (CJ) filed a $500 million wrongful death lawsuit against the alleging that LAPD officers were responsible for Wallace's murder. Retired LAPD Officer alleged that, the head of, hired fellow gang member Wardell 'Poochie' Fouse to murder Wallace and paid Poochie $13,000.

He also alleged that Theresa Swan, the mother of Knight's child, was also involved in the murder, and was paid $25,000 to set up meetings both before and after the shooting took place. In 2003, Poochie himself was murdered in a drive-by by rival gang members. Contents. Prior events Christopher Wallace traveled to Los Angeles, California in February 1997 to promote his upcoming second studio album, and to film a for its lead single, '. On March 5, he gave a radio interview with on 's, in which he stated that he had hired security because he feared for his safety. Wallace cited not only the ongoing and the six months prior, but his role as a high-profile in general, as his reasons for the decision.

Life After Death was scheduled for release on March 25, 1997. On March 7, Wallace presented an award to at the in Los Angeles and was booed by some of the audience. The following evening, March 8, he attended an after-party hosted by and at the in West Los Angeles. Other guests included, and members of the and gangs. Shooting On March 9, 1997, at 12:30 a.m. , Wallace left with his entourage in two to return to his hotel after the closed the party early because of overcrowding.

Wallace traveled in the front passenger seat alongside his associates Damion 'D-Roc' Butler, member, and driver Gregory 'G-Money' Young. Combs traveled in the other vehicle with three bodyguards. The two SUVs were trailed by a carrying ' director of security. By 12:45 a.m. , the streets were crowded with people leaving the event. Wallace's SUV stopped at a red light on the corner of Wilshire Boulevard and South Fairfax Avenue just 50 yards (46 m) from the museum.

A dark-colored pulled up alongside Wallace's SUV. The driver of the Impala, a black male dressed in a blue suit and bow tie, rolled down his window, drew a 9 mm blue-steel pistol and fired at the Suburban; four bullets hit Wallace. Wallace's entourage rushed him to, where doctors performed an emergency, but he was pronounced dead at 1:15 a.m. He was 24 years old. His was released to the public in December 2012, fifteen years after his death. According to the report, three of the four shots were not fatal. The first bullet hit his left forearm and traveled down to his wrist; the second hit him in the back, missing all vital organs, and exited through his left shoulder; and the third hit his left thigh and exited through his inner thigh.

The report said that the third bullet struck 'the left side of the scrotum, causing a very shallow, 3⁄ 8 inch 10 mm linear laceration.' The fourth bullet was fatal, entering through his right hip and striking several vital organs, including his, and the upper lobe of his left, before stopping in his left shoulder area. Wallace's death was mourned by fellow hip hop artists and fans worldwide. Rapper felt at the time of Wallace's death that his passing, along with that of, 'was nearly the end of rap.' Investigation Immediately following the shooting, reports surfaced linking Wallace's murder with six months earlier, due to similarities in the drive-by shootings and the highly publicized East Coast–West Coast hip hop feud, of which Shakur and Wallace had been central figures. Media reports had previously speculated that Wallace was in some way connected to Shakur's murder, though no evidence ever surfaced to seriously implicate him.

Shortly after Wallace's death, writers and Matt Lait reported that the key suspect in his murder was a member of the Southside Crips acting in service of a personal financial motive, rather than on the gang's behalf. The investigation stalled, however, and no one was ever formally charged.

In a 2002 book by, called LAbyrinth, information was compiled about the murders of Wallace and Shakur based on information provided by retired LAPD detective. In the book, Sullivan accused Suge Knight, co-founder of Death Row Records and a known Bloods affiliate, of conspiring with corrupt LAPD officer to kill Wallace and make both deaths appear to be the result of the rap rivalry. The book stated that one of Mack's alleged associates, Amir Muhammad, was the who killed Wallace.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/47816289/life_after_death_star_by_plushgiant-d9e42i6.0.0.jpg)

The theory was based on evidence provided by an and the general resemblance of Muhammad to the generated during the investigation. In 2002, filmmaker released a documentary, based on information from the book. Described Broomfield's low-budget documentary as a 'largely speculative' and 'circumstantial' account relying on flimsy evidence, failing to 'present counter-evidence' or 'question sources.'

Moreover, the motive suggested for the murder of Wallace in the documentary—to decrease suspicion for the Shakur shooting six months earlier—was, as The New York Times put it, 'unsupported in the film.' An article published in by Sullivan in December 2005 accused the LAPD of not fully investigating links with Death Row Records based on Poole's evidence. Sullivan claimed that Combs 'failed to fully cooperate with the investigation', and according to Poole, encouraged Bad Boy staff to do the same. The accuracy of the article was later challenged in a letter by the Assistant Managing Editor of the Los Angeles Times, who accused Sullivan of using 'shoddy tactics.' Sullivan, in response, quoted the lead attorney of the Wallace estate calling the newspaper 'a co-conspirator in the cover-up.' In alluding to Sullivan and Poole's theory that formed the basis of the Wallace family's dismissed $500 million lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles, The New York Times wrote: 'A cottage industry of criminal speculation has sprung up around the case, with documentaries, books and a stream of lurid magazine articles implicating gangs, crooked cops and a cross-country rap rivalry,' noting that everything associated with Wallace's death had been 'big business.'

More recently, a Hollywood film was produced based on the Poole's investigation and Sullivan's book:, starring as Poole, is scheduled to be released in 2018. In examining Sullivan's assertion that the Los Angeles Times was involved in a cover-up conspiracy with the LAPD, it is instructive to note that conflicting theories of the murder were offered in different sections of the Times.

The Metro section of the Times wrote that police suspected a connection between Wallace's death and the, consistent with Sullivan and Poole's theory. The Metro section also ran a photo of Muhammad, identified by police as a mortgage broker unconnected to the murder who appeared to match details of the shooter, and the paper printed his name and driver's license. But Chuck Philips, a staff writer for the Business section of the Times who had been following the investigation and had not heard of the Rampart–Muhammad theory, searched for Muhammad, whom the Metro reporters could not find for comment. It took Philips only three days to find Muhammad, who had a current ad for his brokerage business running in the Times. Muhammad, who was not an official suspect at the time, came forward to clear his name. The Metro section of the paper was opposed to running a retraction, but the business desk editor, Mark Saylor, said, 'Chuck is sort of the world's authority on rap violence' and pushed, along with Philips, for the Times to retract the article.

The May 2000 Los Angeles Times correction article was written by Philips, who quoted Muhammad as saying, 'I'm a mortgage broker, not a murderer' and asking, 'How can something so completely false end up on the front page of a major newspaper?' The story cleared Muhammad's name. A later 2005 story by Philips showed that the main informant for the Poole-Sullivan theory was a with admitted memory lapses known as 'Psycho Mike' who confessed to. John Cook of noted that Philips' article 'demolished' the Poole-Sullivan theory of Wallace's murder. In the 2000 book, investigative journalist and author suggested that Wallace and Shakur's murders might have been the result of the East Coast–West Coast feud and motivated by financial gain for the record companies, because the rappers were worth more dead than alive. The criminal investigation into Wallace's murder was re-opened in July 2006 to look for new evidence to help the city defend the civil lawsuits brought by the Wallace family.

Retired LAPD detective, who worked for three years on a gang task force that included the Wallace case, alleges that the rapper was shot by Wardell 'Poochie' Fouse, an associate of Knight, who died on July 24, 2003, after being shot in the back while riding his motorcycle in. Kading believes Knight hired Poochie via his girlfriend, 'Theresa Swann,' to kill Wallace to avenge the death of Shakur, who, Kading alleges, was killed under the orders of Combs.

In December 2012, the LAPD released the autopsy results conducted on Wallace's body to generate new leads. The release was criticized by the long-time lawyer of his estate, Perry Sanders Jr., who objected to an autopsy. The case remains officially unsolved. Lawsuits Wrongful death claim In March 2006, Wallace's mother Voletta filed a against the City of Los Angeles based on the evidence championed by Poole. They claimed the LAPD had sufficient evidence to arrest the assailant, but failed to use it. David Mack and Amir Muhammad (a.k.a. Harry Billups) were originally named as defendants in the, but were dropped shortly before the trial began after the LAPD and dismissed them as suspects.

The case came for trial before a jury on June 21, 2005. On the eve of the trial, a key witness who was expected to testify, Kevin Hackie, revealed that he suffered memory lapses due to psychiatric medications. He had previously testified to knowledge of involvement between Knight, Mack, and Muhammed, but later said that the Wallace attorneys had altered his declarations to include words he never said. Hackie took full blame for filing a false declaration. Several days into the trial, the plaintiffs' attorney disclosed to the Court and opposing counsel that he had received a telephone call from someone claiming to be a LAPD officer and provided detailed information about the existence of evidence concerning the Wallace murder.

The court directed the city to conduct a thorough investigation, which uncovered previously undisclosed evidence, much of which was in the desk or cabinet of Det. Steven Katz, the lead detective in the Wallace investigation. The documents centered around interviews by numerous police officers of an incarcerated informant, who had been a cellmate of imprisoned Rampart officer for some extended period of time. He reported that Perez had told him about his and Mack's involvement with Death Row Records and their activities at the Peterson Automotive Museum the night of Wallace's murder. As a result of the newly discovered evidence, the judge declared a and awarded the Wallace family its attorneys' fees. On April 16, 2007, relatives of Wallace filed a second wrongful death lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles.

The suit also named two LAPD officers in the center of the investigation into the Rampart scandal, Perez. According to the claim, Perez, an alleged affiliate of Death Row Records, admitted to LAPD officials that he and Mack (who was not named in the lawsuit) 'conspired to murder, and participated in the murder of Christopher Wallace'. The Wallace family said the LAPD 'consciously concealed Rafael Perez's involvement in the murder of. Granted to the city on December 17, 2007, finding that the Wallace family had not complied with a California law that required the family to give notice of its claim to the State within six months of Wallace's death. The Wallace family refiled the suit, dropping the state law claims on May 27, 2008. The suit against the City of Los Angeles was finally dismissed in 2010. It was described by The New York Times as 'one of the longest running and most contentious celebrity cases in history.'

The Wallace suit had asked for $500 million from the city. Defamation On January 19, 2007, a friend of Shakur who was implicated in Wallace's murder by the Los Angeles affiliate and in 2005, had a lawsuit regarding the accusations thrown out of court. See also. References. March 12, 1997. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

^ Bruno, Anthony 2007-04-07 at the. Court TV Crime Library. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

^ Sullivan, Randall (December 5, 2005). Rolling Stone. Archived from on April 29, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2006. Purdum, Todd S. (March 10, 1997). Retrieved February 23, 2009.

nevereatshreddedwheat # (March 9, 1997). Retrieved December 31, 2013. Horowitz, Steven J.

(December 7, 2012). Retrieved December 7, 2012. Smith, Alex M. (August 18, 2014).

Las Vegas Sun. March 10, 1997. Philips Laitt, Chuck Matt (March 18, 1997). Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved September 18, 2013. ^ Fuchs, Cynthia (September 6, 2002). ' PopMatters. Retrieved January 2, 2007. ^ Serpick, Evan (April 12, 2002). Entertainment Weekly.

Retrieved January 2, 2007. ^ Philips, Chuck Los Angeles Times, February 7, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2007. ^ Philips, Chuck (June 20, 2005). Retrieved October 3, 2013. ^ Leland, John (October 7, 2002).

New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

Duvoisin, Marc; Sullivan, Randall (January 12, 2006). Rolling Stone. Archived from on August 17, 2007. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

^ SISARIO, Ben (April 19, 2010). New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2013. ^ Cook, John (May 23–26, 2000). Brills Content.

Archived from on 2012-08-09. Retrieved August 1, 2012. Trounson, Rebecca (February 22, 2012). Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved April 28, 2013. Philips, Chuck (May 3, 2000). Los Angeles Times. ^ Cook, John. Reference tone. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

Philips, Chuck (June 3, 2005). Retrieved September 15, 2013.

Bruno, Anthony. Archived from on 2013-11-10. Retrieved December 31, 2013. Philips, Chuck (July 31, 2006).

Los Angeles Times. Archived from on October 21, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

Associated Press. August 3, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

Kenner, Rob (March 9, 2012). Retrieved September 26, 2012. Quinn, Rob (October 4, 2011).

Retrieved September 26, 2012. Wolfe, Roman (December 8, 2012). Retrieved December 9, 2012. Estate of Wallace v. City of Los Angeles, 229 F.R.D. 2005);Reid, Shaheem (July 5, 2005).

Biggie Smalls Death Scenario

Retrieved February 14, 2007. Finn, Natalie (April 18, 2007). Retrieved August 2, 2007.

Estate of Christopher G.L. City of Los Angeles, et al., 2:07-cv-02956-FMC-RZx, slip op. December 17, 2007) (Cooper, J.). Complaint, Estate of Christopher G.L. City of Los Angeles, et al., 2:07-cv-02956-FMC-RZx (C.D. May 27, 2008).

Associated Press. January 20, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2009.